Toshio only draws turtles

by Weltraumbesty / KRP, 10th of October 2025

///

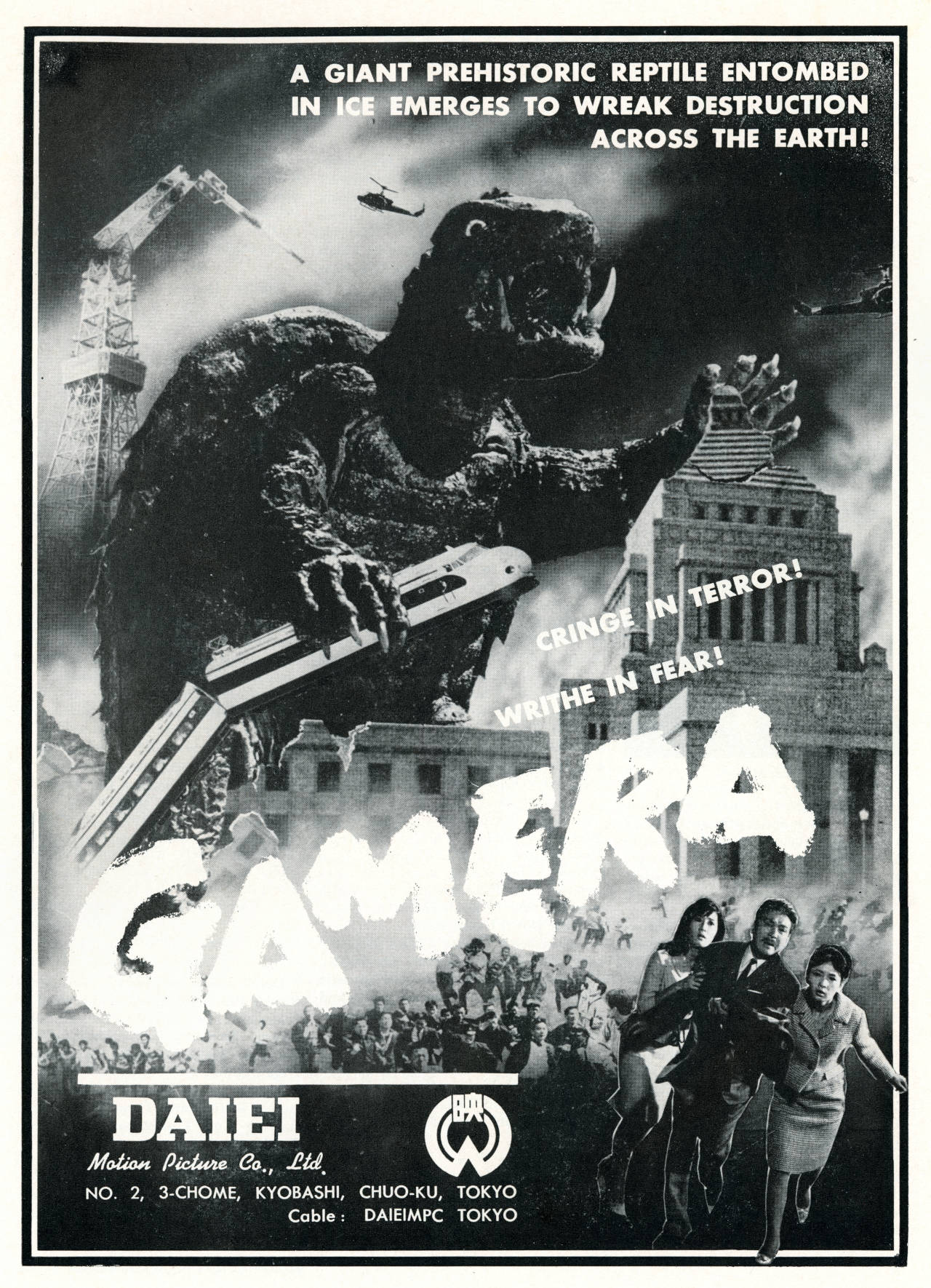

1965’s Giant Monster Gamera is a strange film, melancholic and uneasy and existentialist and, like bittersweet nostalgia, curiously familiar. The first kaiju eiga to be pitched into direct conflict with Toho Company’s steady slate of special effects action fantasies (which had ruled in a solitary genre hegemony for better than a decade by then), Gamera was birthed by presidential decree from Daiei Motion Picture Company’s ill-equipped Tokyo studio, which had no extant facilities to undertake the scale of effects production it required, by a novice director and a production staff with little to no experience working in the genre. Heavily inflected with the idiosyncratic desires of dictatorial Daiei president Masaichi Nagata (perhaps inspired to create a giant flying turtle by his son Hidemasa, though perhaps not —— the lineage of Gamera is murky with ill remembrance and mired in contradictory accounts), who dictated the film’s forlorn tone so as to appeal better to its young target audience, the finished film feels every bit the freshman effort that it is and is largely the better for it.

The basics of the story, obviously influenced by Warner’s germinal giant monster thriller The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (which Daiei had distributed a decade prior to Gamera’s production), follows zoologist Dr. Hidaka (prolific film and television actor and “wasei Marcello Mastroianni”, Eiji Funakoshi), his daughter, and their news photographer companion, who become the sole survivors of an expedition investigating legendary Atlantean turtles when one of those very creatures, loosed from the ageless ice by near-apocalyptic Cold War happenstance, destroys their ship and disappears. Dubbed Gamera (“It is the devil’s envoy!”) in accordance with local tradition, the fateful trio follow the fire-eating monster as he makes landfall in Japan, wrecking a lighthouse and feasting at a geothermal plant before stumbling through the defenseless edifices of modern Tokyo.

Though familiar enough in the broad strokes, in its details Gamera is anything but. Screenwriter Niisan Takahashi (who would pen seven further screen outings for Daiei’s largest star) throws just about everything at the wall in an effort to bridge the functions of storytelling with domineering president Nagata’s eccentric demands for the project, and most of it sticks just fine. His screenplay prefigures the occult boom of the latter 20th century with its preoccupation on flying saucer flaps and Atlantean mythology (the ‘90s trilogy of films would take these occult influences far further) and presents what feels like the first giant monster entirely of the Space Age —— an impossibly gigantic saber-toothed turtle that feasts on flame (atomic and otherwise) and withdraws its limbs to fly by jet propulsion. Takahashi’s real innovation, however, is in how his work internalizes and reflects the interests of its intended audience. To the adult cast of Gamera the monster is a threat, hungry and insatiable, an aimless creature of destruction that promises to bleed the Earth dry of its energy resources and raise all hell for humanity in the process. But to the children watching the picture, perhaps with daydreams of being the first of their class to walk on the moon, Gamera is something else entirely. A menace, sure, and a noisy one besides, and with a regrettable penchant for inflicting massive civilian casualties. But the monster is also hopelessly lost, loosed into a world unsuited to him through no fault of his own, a world in which he seems to have no place, alone and hungry and fundamentally misunderstood by everyone around him. To the children sitting in those darkened theater seats, hearing a monster’s melancholic cry as the adult world falls fitfully and painfully and ceaselessly upon him, Gamera is them.

It is no great leap to suggest that children love and relate to monsters, but Takahashi’s screenplay embraces the concept like few others before or since. Disillusioned adults may rule the action, lobbing experimental freeze bombs and drawing up top secret international plans to launch the monster into space, but the perspective of the film is not theirs at all. Neither Takahashi’s writing nor the direction of Noriaki Yuasa, himself disillusioned from a youth spent in the adulterous surroundings of the entertainment industry (and tasked with directing Gamera when no one else at Daiei would take what promised to be a career-ending assignment), is concerned with such unsentimental and cynical perspectives, and offer an alternative frame of reference in their stead; That of a boy who lives with his older sister and widowed father at an isolated lighthouse in Hokkaido. A boy named Toshio, who only draws turtles.

Toshio is the ur-Gamera child, both literally and figuratively, the patient zero of kaiju eiga’s youthful fan base crossing the fourth wall and becoming primary players in the stories they loved (this trend was already evident in anime and manga, and would continue throughout the original Gamera films and, again, find a more contemporary iteration in the ‘90s Gamera trilogy). He also reads like something of a laundry list of diagnostic criteria that wouldn’t hit the DSM for decades yet —— isolated and quiet and introspective, friendless (save for his pet turtle, Chibi) and disinterested in other children, rigid in his thought (particularly regarding turtles, whom he sees as an indisputable moral good) and preternaturally fixated on his favorite animal across all aspects of his life. It’s a strength of the film (and of Yuasa and Takahashi’s other collaborative work, which iterates on like themes throughout) that Toshio does not come across as unhappy for any of these social peculiarities. His sadness instead finds its roots in those around him, people who chide him for his fixations or mock him for his eccentric behavior. Adults, incurious and jaded, who have no interest whatever in seeing the inherent goodness of turtles, gigantic or otherwise.

Gamera introduces Toshio vicariously by way of a beach-side chat between his older sister and a frustrated schoolteacher. We learn that his behavior —— ignoring the other children and constantly drawing or writing about turtles —— is becoming disruptive, not the least because he has begun bringing his pet Chibi to class with him. His devotion to the animal is causing friction at home as well, where he is formally introduced in the process of stealing away bits of his dinner to feed to the turtle later. This is the final straw for his family, who promptly demand that Toshio release the animal (with the express threat that if he does not, his father will do so while he’s at school). “We’re thinking of your future,” they say. “It would be terrible if you grew up to hate human beings. People can’t live alone!” And so Toshio regretfully agrees to sacrifice a core part of himself to the altar of social normalcy.

As evening settles on the seaside scene Toshio lays down among the tall grass, aimless and anxiously fidgeting, his loathsome chore done. Chibi has been set free (among some rocks, loosely organized into a home), but even as Toshio quietly mourns the absence of his only friend fortune visits another upon him —— the devil’s envoy, Gamera! Fresh from causing a worldwide flying saucer flap and hungry for fire once more, the 200-foot turtle arrives at that secluded cape to the fearful excitement of Toshio and the abject terror of the adults around him. In a flash the boy has climbed the lighthouse steps, itching for a closer look, but his curiosity is disastrously met with Gamera’s own. The creature reaches out, clumsily, half-collapsing the lighthouse and dooming Toshio, who is left dangling from its railings. His grip loosens and he screams for help, his fate obviously sealed, but as Toshio plummets towards his certain death Gamera reaches out again, catching the boy in the palm of his hand and gently (by giant turtle standards, at least) delivering him to his relieved family below. “Gamera saved you!” his sister tearfully relates as Toshio sits, rattled and dumbfounded and pensive with reflection about a deathly circumstance narrowly avoided and the frightening, friendly monster who helped him.

From 1967’s Gamera vs. Gyaos onward the relationship of Gamera to the children who love him becomes relatively straight forward, a series of comparatively uncomplicated stories that find Gamera protecting his devoted young fans from various fell troubles (whether it’s fiendish vampire bat-monsters wanting to eat them, deceitful alien women wanting to eat them, or autocratic narcissistic space-sharks wanting to eat them…) and saving the world (or the World’s Fair, or Kamogawa Sea World…) in the process. While Gamera lays the groundwork for this quite adeptly (ignored though it may be for the film’s first sequel in ‘66), its presentation of the relationship between Toshio and Gamera (and its depiction of Gamera himself) is far less safe and far more nuanced than those that would follow.

After his lighthouse rescue (and after deciding, in his naive way, that the released Chibi had perhaps transformed into Gamera) Toshio becomes a boy obsessed. When Gamera appears at a geothermal plant and the first battle lines are drawn by the Self Defense Force, Toshio is there, proclaiming the monster’s inherent goodness to anyone who will listen. When the military ultimately stands down out of well-founded concerns that their attacks are needlessly destroying property and feeding, as opposed to repelling Gamera, Toshio takes it as a personal affirmation. Even as the monster lays waste to block after block of metropolitan Tokyo, razing Tokyo Tower to its very foundations and killing untold thousands, Toshio keeps the faith. From his temporary home he pleads with the wayward creature, chastising Gamera for his ill behavior as Tokyo burns just off screen.

Soon thereafter his fascination with the monster leads again to near disaster as Toshio shirks an evacuation order to visit Gamera, who is being held in relative peace at a bay-side fuel yard by a steady diet of tank cars, fed to him by the authorities as they rush to complete the top secret Z-Plan. There Toshio hitches a ride on one of the cars, intent on meeting Gamera face-to-face once more and oblivious to the danger all around him. Only the swift action of the foreman saves him from utter annihilation when the monster, helplessly fixated on his own enormous appetite, explodes the tanker and nearly atomizes his devotee in the process. The foreman dutifully carries the miraculously unharmed Toshio to safety and, though clearly exasperated by the boy’s actions, politely sends him on his way. The other workers mock the child and his protestations (“Gamera is my friend!”), and Toshio only becomes more isolated and insular, more dedicated to following the monster. So much so that when Z-Plan is finally put to action he stows away in a ship’s hold so that he can witness it all first hand (and perhaps stop Gamera from falling for it at all).

It all ends peacefully enough when Z-Plan is revealed for what it is —— a daikaiju-sized clandestine space program that has been hastily transfigured into a mission to fly Gamera to the distant safety of Mars. Toshio is so taken with the feat of Space Age super-science that it sparks within him a newfound purpose. As the world celebrates Gamera’s Earthly eviction the boy vows to become a scientist, “Just like you, Dr. Hidaka!”, that he might someday voyage into space himself… to see Gamera again, of course.

Gamera ends with a message of international cooperation, intoned by an excited radio announcer as the Z-Plan rocket ascends, but the real point of the picture lies with its sensitive portrayals of Toshio and the giant monster he adores, a pair of social outliers (albeit at markedly different scales) that are far more relatable than the comparatively pat sci-fi dramatics that surround them. Toshio (and perhaps Gamera as well) remains something of an unsung cinematic champion of neurodiversity representation, well ahead of his time in many respects, but perfectly situated as a reflection of a core audience of monster-obsessed youth on the eve of Japan’s first monster boom. I certainly saw something of myself there, 25 years after the fact, as a burgeoning monster movie fan watching Gamera for the first time on a barely operable VHS from Blockbuster. For a time thereafter, a bit like Toshio, I only drew turtles, and Gamera had a way of sneaking into my creative writing assignments well through high school. The more things change…

Giant Monster Gamera was an absolute smash upon release, racking up hefty box office pre-sales and serving as a Hail-Mary for Daiei, which was even then struggling against years of fiscal mismanagement and otherwise questionable leadership. The company put other monster-oriented series into production at a pace that was faster than it could really afford (the three Daimajin films, all released in ‘66, and a further trilogy of period yokai fantasies from ‘68-’69), none of which would survive the dual blows of declining audience and rising production costs. But Gamera, friend of all children, would persist against the odds until Daiei’s catastrophic collapse in 1971, with Noriaki Yuasa, Niisan Takahashi and an enthusiastic and overworked slate of creative personnel all doing their absolute utmost to keep both the profitable series and the floundering film company afloat despite the Nagatas’ (father and son, both) fatal errors in management and the decline of the industry as a whole.

The friend of all children turns 60 this November 27th, the date Giant Monster Gamera originally debuted in Japanese cinemas, an anniversary that is being met with a theatrical and home video revival of the 1965 film from a fresh 4k restoration and a month long “Gamera EXPO” event in Tokyo. The character has been revived innumerably over the course of those sixty long years, in film and in animation, comic books, novels, commercial endorsements and on and on, been privileged roasting material for three different generations of Mystery Science Theater 3000 (all the way back to its germinal UHF days) and won the hearts and minds of countless young people through television syndication, home media reissues, and a not inconsiderable amount of video piracy. And why not? The original seven-film series (for which 1980’s Super Monster served as an appropriately threadbare post-bankruptcy capstone) feels like the last gasp of uninhibited joy to escape the misery of Daiei’s decline, and Giant Monster Gamera remains special among them. It’s scrappy and sensitive and irrevocably sincere, and introspective of its own genre to the point of metatextuality —— it’s as much a film about giant monster fandom as it is a giant monster film in its own right. Though it’s forever threatening to show its seams Giant Monster Gamera never the less works, held together by nothing less than the pure dogged determination of a devoted creative staff that worked itself to the bone to bring one self-absorbed film executive’s absurd dream to life. In the process they managed to create something interesting, something lasting, something that has influenced and inspired countless other creatives in the decades since, and in that respect more than any other Giant Monster Gamera is a rarefied success indeed.

Happy 60th birthday, Gamera.

///

~ Weltraumbesty / KRP

← previous // home ↵ // next →

if you enjoyed this shit then please consider throwing us a buck or two. we wander the wastes of intergalactic space in search of a new home, free from war and traffic accidents, and are powered by coffee alone. thank you.

© Weltraumbesty